On September 26th, a group of idealistic students from the leftist Raúl Isidro Burgos Rural Teachers College of Ayotzinapa, Mexico, traveled to Iguala to protest discriminatory hiring practices. The group had commandeered buses and blocked a road, so they expected a police reaction, possibly beatings or detention. They did not expect an all-out assault from municipal police officers and unidentified gunmen shooting imprecisely and indiscriminately. Though eyewitness accounts of details vary, in total six were killed and 43 more went missing.

Before their deaths, the students were turned over to a local drug cartel and gang with strong ties to Iguala’s government known as the Guerreros Unidos. About a week later on October 5th , investigators found a mass grave with 28 bodies, but upon consulting further forensic tests authorities could not match the bodies found with those of the student protesters. , to state police the bodies, charred beyond recognition, were burned alive. It was at this point that Mayor José Luis Abarca Velázquez and his wife María de los Ángeles Pineda Villa—accused of direct participation in the two mass torture murders— fled, only to be arrested in Mexico City a month later. Later, on November 7th, Mexico’s attorney general announced that three Geurreros Unidos suspects had confessed to burning the bodies of the students and dumping their ashes in a river. Meanwhile, the number of people implicated in the tragedy has continued to grow; 50 suspects and more than 20 police officers have now been arrested.

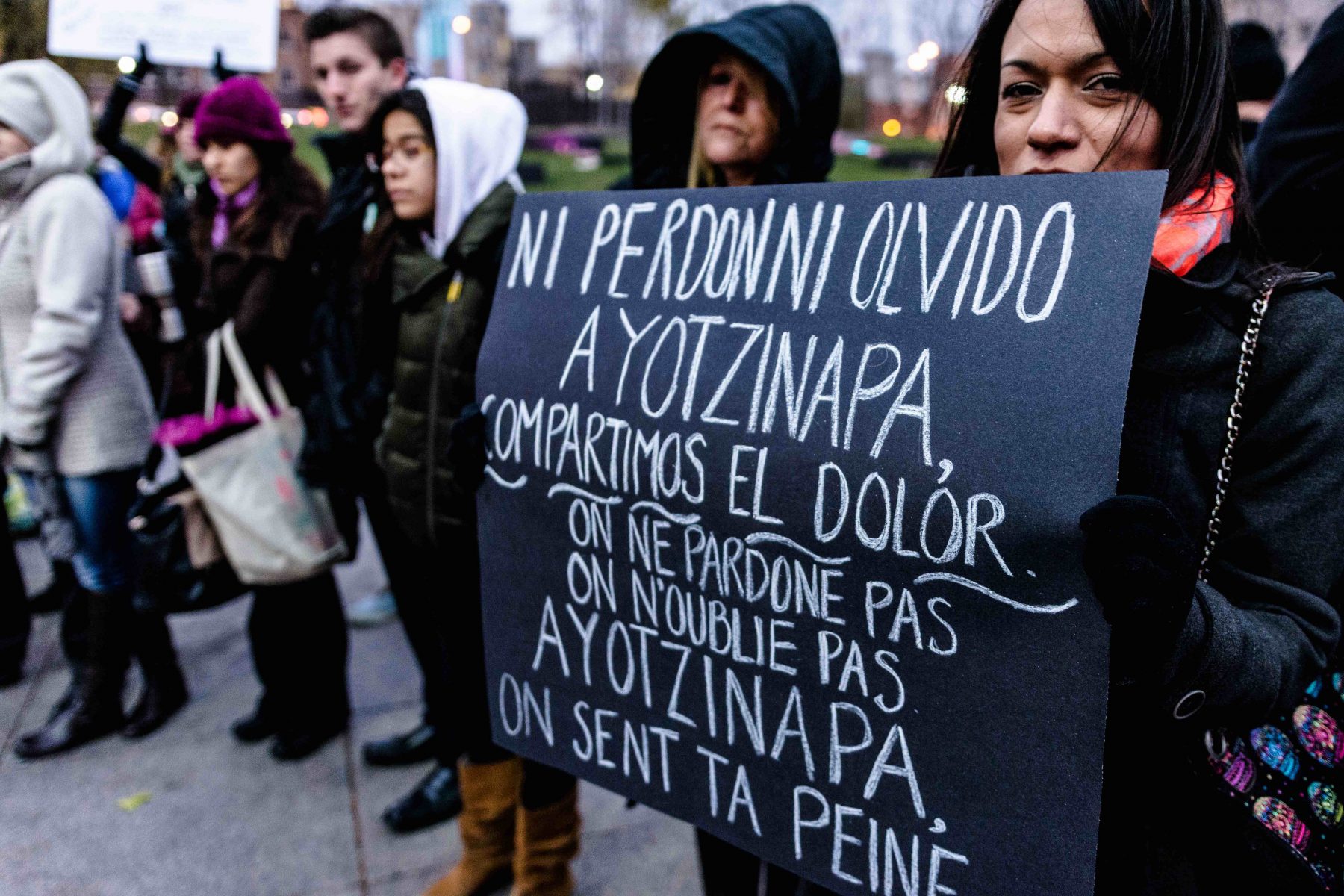

Shockingly, there is little unique about this tragedy. The method of killing and the lack of government action taken has become routine in the ongoing Mexican drug war; in December 2011, authorities did nothing about the killing of two Ayotzinapa students and the torture of 20 more, and in May of 2013, three social leaders were abducted and murdered, and though the municipal president of Iguala was likely involved federal authorities never intervened. The entire chain of events has lead to violent protests all over Mexico, in Mexico City, Guerrero state, and Iguala especially. The off-the-cuff phrase Attorney General Jesús Murillo Karam spat out at the crowd following an unproductive press conference, “Ya me Canse” (meaning “Enough, I’m tired,”) has become the rallying cry of outraged citizens who are sick of drug cartel money and personnel illicitly infiltrating official government.

More horrific details of the past month will likely surface, but it’s possible that we will never know all the details of what happened. We do know, however, that the government and citizens were aware of the underlying problems and the extent to which the Guerreros Unidos were in control. In an interview with the Huffington Post, Alejandro Encinas, a senator from the mayor’s Democratic Revolution Party, said of the Mayor and his wife, “Everyone knew about their presumed connections to organized crime…. Nobody did anything, not the federal government, not the state government, not the party leadership.”

The Guerreros Unidos attack on the students could have been a response to the students’ refusal to pay the cartel or it could have been out of fear that the protests would disturb Pineda’s speech. Regardless, the massacre was not a proportionate response. Clashes between the teachers college and the local government have existed for years, but the involvement of the Guerreros Unidos has added another unpredictable element to the tension. The college is one of very few groups willing to stand up to the drug cartel violence, and it tends to use aggressive methods of protest, such as hijacking buses, throwing rocks at police and stopping traffic along major roads to elicit donations. The group already operates under the assumption that the government will not do its job honestly and officials will always act selfishly. Following last month’s tragedy, government will only become more synonymous with corruption within the small indigenous communities whose youths make up the college’s student body.

As more details of the mass kidnappings bubble to the surface, it becomes more and more evident that parts of Mexico operate under the heavy political influence of drug cartels. A narco-state can certainly function in many day-to-day ways no differently than an ordinary government would, and as long as citizens tolerate the occasional beatings and tortures, ignoring drug cartels is the path of least resistance. But a government machine, controlled at the lowest level by drug cartels, means more than just corruption; it means that that anyone at any point is unsafe, and no one is accountable. It also means that though Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto can make reforms to combat drug trafficking, his efforts will not be visible at the level of the ordinary citizen. The conflation of drug cartel and government leaves deep scars on the attitude of citizens towards the state. Citizens become afraid to report crimes and apathetic to violence. And as corruption lingers, it has become, and will continue to be, a lasting expectation.