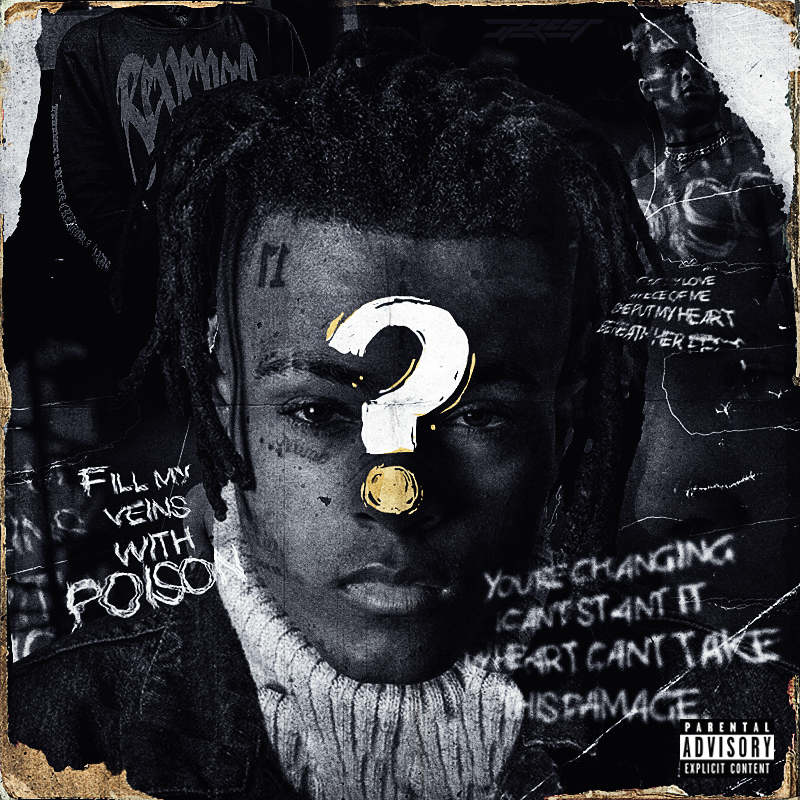

Two days after twenty-year-old Floridian rapper XXXTentacion was shot in Miami during a robbery, his final music video was released. “SAD!”, slickly produced and full of rather obvious symbolism, opens on a pair of eyes, and then with X himself strolling down the aisle of a church. As he approaches an open casket at the pulpit, we catch a glimpse of X’s signature locks, half bleached-blonde and pulled to the top of his head, peeking out from the top of the coffin. The artist is attending his own funeral. The video moves between scenes of X fighting himself and X sitting before a dark, cloaked figure who speaks to him in a distorted voice. Throughout, subtitles that read somewhere between a dating app questionnaire and an anime script discuss battling demons, positive energy, and self-satisfaction.

The final image is a black screen that reads in white font: “Long Life Prince X,” a mantra that has been chanted and typed by his fans across almost every social media platform and repeated again during his funeral vigil-turned-riot.

Unsurprisingly, the untimely death of an artist induces shock and collective heartbreak for dedicated fans, especially if their death was sudden, violent, or self-inflicted. This feeling seems especially poignant for musical artists who sing of frustration, pathos and heartbreak, such as X, Kurt Cobain and Chester Bennington. For young and vulnerable fans, one more individual who seemed to relate to and ease their struggle has been removed from the world. And their mourning takes many forms—eight thousand fans passed through the Florida Panthers’ stadium to see X in a coffin (In death, as in life, celebrities have little control over the exposure of their intimate moments), or participate in vigils. An artist’s music experiences a resurgence and X’s “SAD!” broke the Spotify streaming records—his posthumous commercial success arguably surpassing what X could find in his own lifetime.

We honor our dead artists in another way: by shifting our perceptions of them. At best, this takes the form of a willful forgetting of minor offenses and, at worst, involves a rewriting of history that may paint an oppressor as a victim or incorrectly assign martyr status. An artist’s crimes become overshadowed by the shock of their passing, and the artist’s controversy is dulled by the fact that they aren’t alive to continue to perpetuate violence or to respond to accusations.

We largely overlook Frank Sinatra’s ties to organized crime, or Chuck Barry’s indecent experiences with women, or Marvin Gay’s domestic abuse. And we return, again, to X. In life he was a highly controversial and problematic figure; his work was often overshadowed by, or put into direct conversation with, his fraught personal life. X, frequently on the wrong side of the law, was a known abuser of women, including his pregnant ex-girlfriend whom he beat so severely that she required corrective eye surgery and he admitted to nearly killing a gay cellmate in a homophobic attack. Despite X’s violent past, he had spoken at length about his desire to change and control his anger, as well as his struggles with mental illness. And, responses from his fans varied. Some admitted only tacit acceptance of his flaws, others dedicated themselves to the creation of X as a tortured and broken creative genius, and others went so far as to brand his ex-girlfriend’s legal action following X’s assault as “snitching.”

The #MeToo movement shed much needed light on sexual abuse rampant in the entertainment industry and has managed to dethrone serial abusers, no matter their status. However, X’s reckoning never seemed to fully come to fruition. Spotify did remove his tracks from their playlists in accordance with a new, and very unevenly applied, anti-hate policy. This action immediately sparked backlash from artists such as Kendrick Lamar, and X’s songs were quickly reinstated. However, after his death, many fans doubled down on their defense of X’s behavior. Indeed, during X’s vigil, his ex-girlfriend’s offerings were burnt, and she was chased down and beaten by angry fans. Moreover, after X’s death, Spotify released a “This is XXXTentacion” playlist presumably to pay homage to the dead rapper, but so too to capitalize off a highly lucrative spectacle. X’s reckoning, it seems, might never arrive.

With nearly every dead artist, we see certain segments of fans maintain that their icons still live, or, instead, that they died long before and were being impersonated for a lengthy period before this impersonator also died. Reversed tracks reveal hidden messages disclosing the true time of death; John Lennon may be in Canada. A video taken mere minutes after X’s passing circulated, and fans quickly picked apart the thirty seconds, evaluating what tattoos were visible as well as the placement of blood on the body. The conclusion that many reached was that the man shot was not X at all, and the whole affair was part of a hype campaign for the release of his new music. Perhaps these conspiracies reveal our desire to keep dead artists breathing and creating. As “Long live X” may imply, even in death, our favorite artists never truly fade away.

While immortality and martyrdom may stem from untimely death, they do come at a cost. While alive, artists experiment with style and change their subject materials to fit their own arcs of exploration and growth; however, once dead, artists become trapped at a specific point within their artistic metamorphoses. Ultimately, a dead artist is a static one. While suicidal artists did create work that focused on their struggles with mental illness, and artists who died violently often wove narratives of violence into their work, the means of death often becomes disproportionally influential in how the artist’s oeuvre is perceived and what is emphasized in lieu of aesthetic or formal qualities.

X’s “SAD!” video becomes more a dark portent of his own demise than a narrative of two selves at war. And we feel compelled to bracket entirely the message to “change the overall cycle of energy we are digesting” that the subtitles (as well as XXXTentacion’s previous works) advocate for.

Francesca Woodman, the talented young photographer who took her own life at twenty-two following ongoing struggles with mental illness and commercial failure, receives a similar treatment. Many view Woodman’s haunting photographs as an intriguing look into the psyche of a mentally ill woman and read fatality into work from much earlier in her life. Blurred faces and exposed women become evidence of a disturbed mind, and the conversation begins to revolve around psychology rather than the work itself. The aesthetic qualities and innovation that Woodman utilized take a backseat. Tragedy and mental illness did not make Woodman’s work great; her artistic merit made it so.

It is also important to remember that many artists’ work, in some way, touch on mortality. We need not look at artists far outside the pale of mainstream culture to recognize these modern-day memento moris. In The Weeknd’s “Starboy” music video, he strangles the Beauty Behind the Madness version of himself before debuting his new look. In Lana Del Rey’s “Born to Die” music video, she dies in a bloody, fiery car crash, although a later studio album would be entitled Lust for Life. Even Taylor Swift’s upbeat “Look What You Made Me Do” includes a partially decaying Swift in a graveyard. Death and mortality are central themes, but do not dominate these artists’ oeuvres.

As much as immortality and a vindication from previous crimes is an organic outgrowth of fans’ serious dedication and may become a continuation of the types of conversations that happened while an artist was alive, an artist’s worth is also influenced by the market. Once an artist has passed prematurely, advertisers and streaming companies; art critics and art historians begin to craft a tragic narrative to compliment a tragic demise. It perhaps is not the most honest one, nor is it the most respectful to the artist, but, as we see with X, it can prove to be very lucrative.