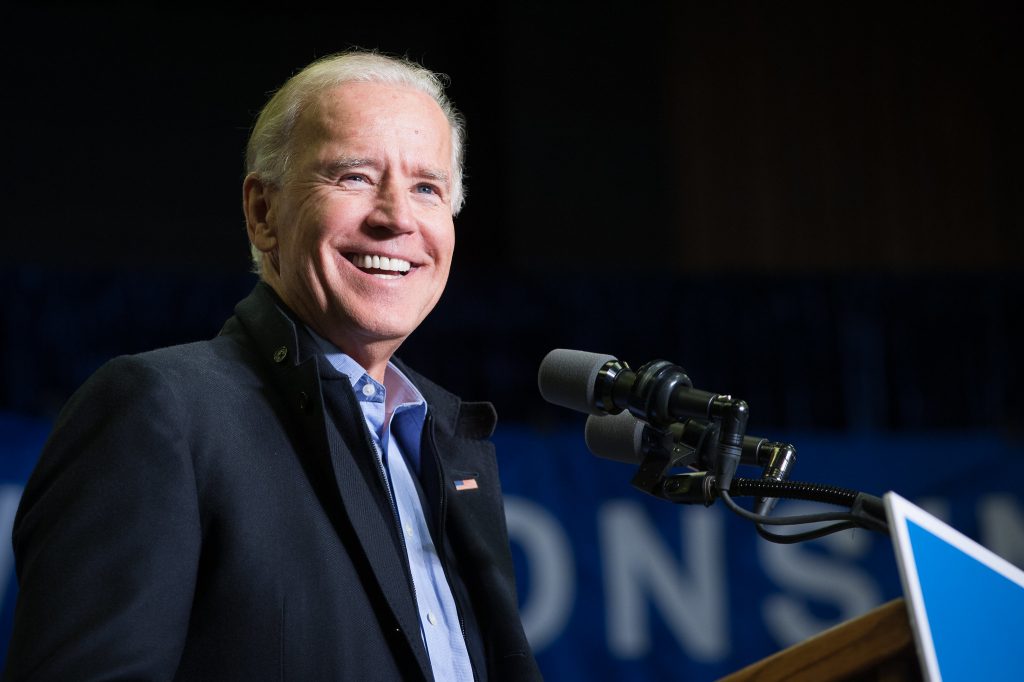

“The election ain’t over until every vote is counted,” Joe Biden said to a drive-in crowd of supporters 12:45 a.m. Wednesday in his hometown of Wilmington, Delaware. “Every time I walked out of my grandpa’s house in Scranton, he would say, ‘Joe, keep the faith.’”

We kept the faith, and Joe has won.

Democrats’ lofty ambitions – blue Florida, blue North Carolina, blue Texas? – may have evaporated, but former vice president Joe Biden indeed has eked out an Electoral College victory. With his nail-biter win of Pennsylvania called Saturday morning, Biden is all but certain to become the forty-sixth president of the United States. His campaign presented a moderate, stable alternative to the volatility of the Trump administration and capitalized on the Covid-19 pandemic to set forth a progressive policy agenda while winning back the Democratic “blue wall.”

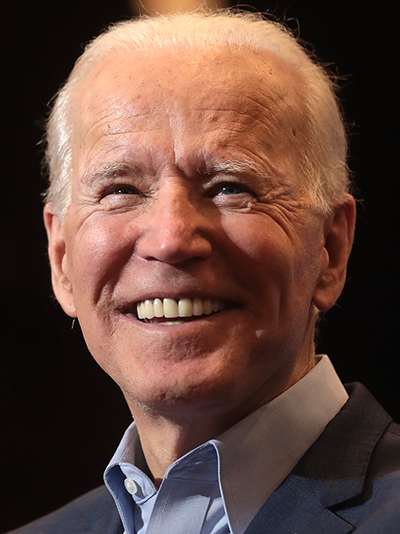

Biden’s life is one of gaffes, personal tragedies, and political setbacks – but also underdog victories. His style of pragmatism and coalition-building combined with statesmanship and old-fashioned competence will define the next four years.

I. JOE IMPEDIMENTA

Biden’s working-class upbringing and Pennsylvania heritage are something of a political asset: they gave him the credibility needed to win back the crucial blue-collar midwestern voters Hillary Clinton lost in 2016. He was born in Scranton, Pennsylvania in 1942. His father was a wealthy business owner who lost everything when business soured and moved the family to Delaware when Joe was 10 to begin selling used cars and cleaning boilers.

Biden went on to attend the University of Delaware for undergrad and Syracuse University for law school. His absence from the so-called “coastal elite” and his modest upbringing helped him to appeal to voters in Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin.

“I’m from Scranton. Jill and I grew up 76ers fans,” he said during a Sunday, Nov. 2 stump speech in Philadelphia. Previewing his Election Night address, he turned on the midwestern charm and mentioned his “grandpop’s house up in Scranton.”

Biden’s final campaign ad of the election emphasized his claim to blue-collar ethos. The 60-second commercial entitled “Hometown” shows scenes of firefighters, cooks, and nurses in Scranton while a voiceover by Bruce Springsteen tells us that Scranton is “more than where Biden’s from, it’s who he’s for.” Springsteen’s “My Hometown” plays in the background.

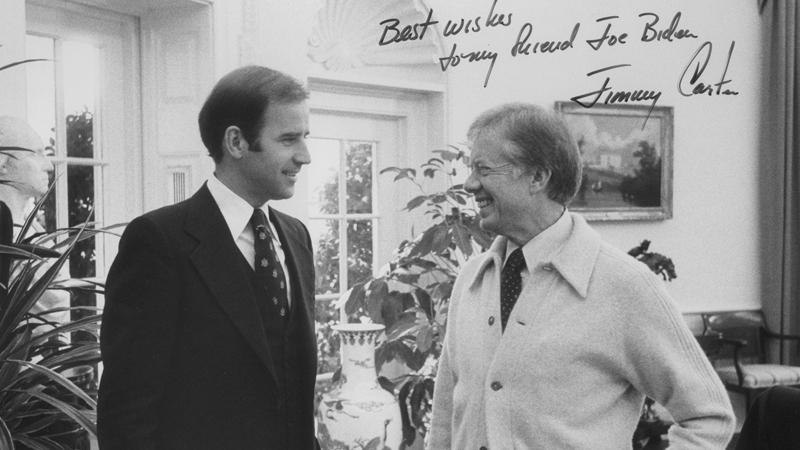

The fact that he lacks the Ivy League educational pedigree common to some of his political peers has led to personal insecurity about how “Amtrak Joe” compares to the likes of the Clintons or his former boss President Barack Obama, says Pulitzer Prize-winner Evan Osnos in Joe Biden: The Life, the Run, and What Matters Now. Biden will be the first Democratic president without an Ivy League degree since Jimmy Carter. (Carter went to the U.S. Naval Academy.) Biden has occasionally fallen into scandals with respect to his educational background: he lied about his law school class rank during his first presidential campaign in 1986 (he graduated seventy-sixth in a class of eighty-five) and subsequently told a reporter “I think I probably have a much higher I.Q. than you do!”

Biden’s strongest memory from his childhood is his overcoming a severe stutter, an experience which endowed him with a strong desire for respect, a hatred of bullying, and a fear of embarrassment. The speech impediment earned him the nickname “Joe Impedimenta.” He reflected in his memoir, “It was like having to stand in the corner with the dunce cap. Even today I remember the dread, the shame, the absolute rage, as vividly as the day it was happening.” When Biden calls Donald Trump “the bully I knew my whole life,” he seethes.

II. A FIFTY-YEAR POLITICAL CAREER

Biden was elected Senator from Delaware in 1972 at the age of 29, just four years out of law school. It was the same year Nixon won reelection in a landslide amid the Watergate scandal. In Biden’s first campaign, he opposed the Vietnam War and emphasized his youth in comparison to a stodgy incumbent. He won by three thousand votes. As an outsider in Washington and a political underdog, Biden embraced the popular views of his constituents and followed the Democratic party line when navigating difficult issues of race, crime, and foreign policy in the 1970s and 80s. Overall, Biden’s political career is that of a hardworking outsider who came to rely on personal relationships and bipartisanship to produce results.

BIPARTISANSHIP AND CENTRISM

Relationship-building in Washington was Biden’s key to a quick rise in the Senate. By 1980, he was chair of the Judiciary Committee, where he lead contentious confirmation hearings in opposition to Clarence Thomas and Robert Bork. As a three-decade member and longtime leader of the Foreign Relations Committee, he frequently collaborated with conservatives, for better or worse.

He became known for forming personal relationships with both with politicians across the aisle and political leaders across the globe. His former national security advisor Julianne Smith said of Biden, “You can drop him into Kazakhstan or Bahrain, it doesn’t matter – he’s gonna find some Joe Blow that he met thirty years ago who’s now running the place.”

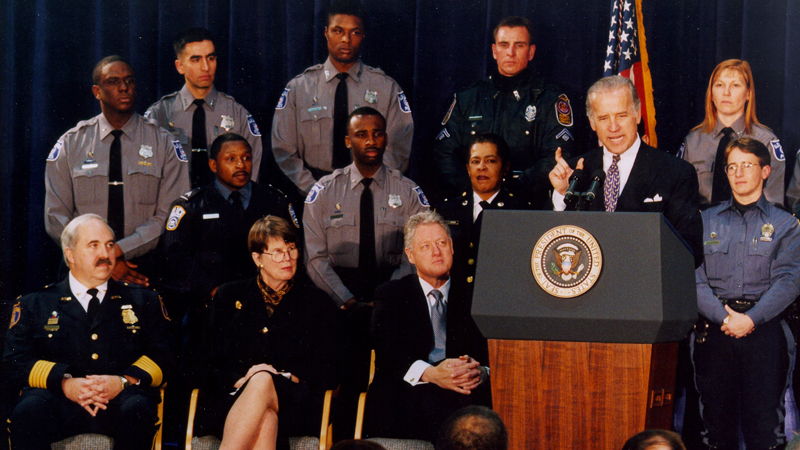

In 1974, Biden described himself as liberal with respect to senior citizens’ issues and healthcare, but conservative about social issues. He conducted his political career as a relative centrist, and his record contains a fair few missteps which dog him still. The ugliest is his authorship of the sweeping 1994 Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act which instituted the draconian three-strikes law in an effort to combat the crime epidemic. The injustices of that bill hurt black communities to this day. Early in his career, he was outspoken against federally mandated busing to remedy de facto segregation. He voted for the Defense of Marriage Act in 1996 and for the Iraq war in 2002, as well as for the deregulation of Wall Street as part of the Democratic party’s embrace of neoliberalism beginning in the 1970s. That record is a tough pill to swallow for progressives this year.

However, when uncertain, he generally followed the “median voter theorem” (broadly, the consensus opinion of his constituents) and listened to the advice of those close to him. The 1994 crime bill was supported by black leaders and community members in its day – including Representative James Clyburn of South Carolina, now the highest-ranking Black member of Congress – who were horrified by the scourge of crack. The bill was not controversial in its time. Busing was controversial nationally, yet Biden’s majority-white Delaware constituency felt fervently that courts should not be able to order it in the absence of de jure segregation. His embrace of the neoliberal “third way” was common to the entire struggling Democratic party beginning in the ‘70s. His record is far from perfect, but Biden admits his failures and learn from his mistakes. “I haven’t always been right,” he said in 2019 about the crime bill. “I know we haven’t always gotten things right, but we’ve always tried.”

Biden is an unapologetic centrist. His career required him to navigate difficult questions; missteps were inevitable. But a president who listens to the will of his constituents and does not promise perfection will be a refreshing change from the current administration.

COMPETENCE

Contrary to his portrayals on Saturday Night Live and in The Onion, Biden has also built a reputation for technocratic competence and attention to detail. Part of this harks back to some of the unabashedly positive achievements of his Senate career. The Violence Against Women Act of 1994 has been called by the ACLU “one of the most effective pieces of legislation enacted to end domestic violence, dating violence, sexual assault, and stalking.” In the Judiciary Committee, he led the hearings in successful opposition to Robert Bork, Ronald Reagan’s 1987 Supreme Court nominee. (To “bork” someone now means to thwart resoundingly a candidate for public office.)

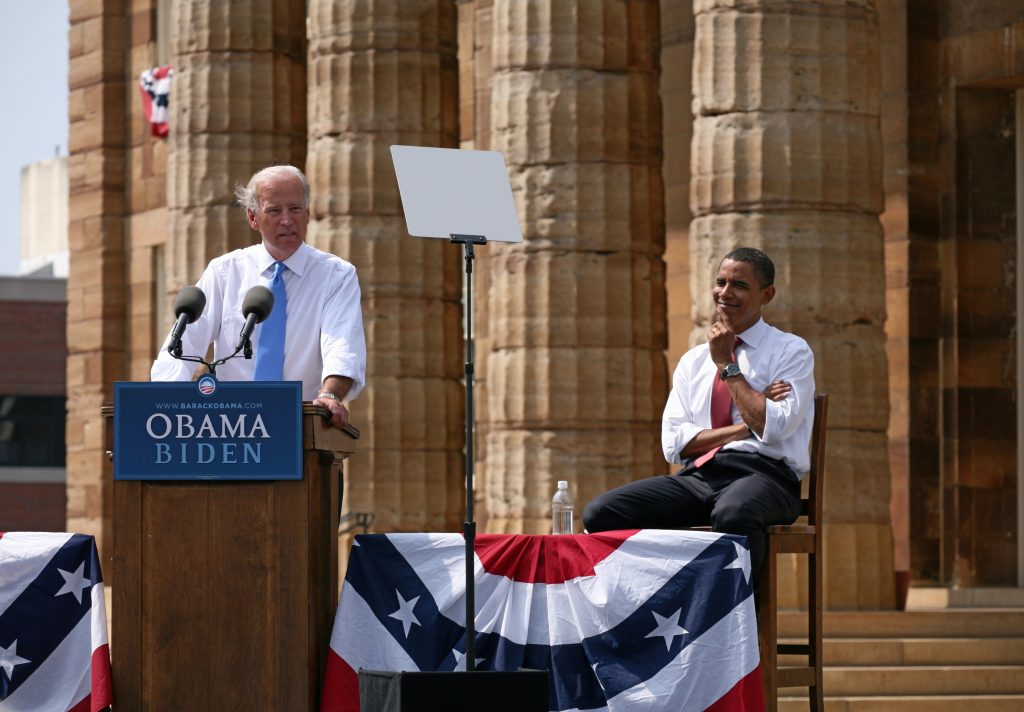

As vice president, he took on significant responsibility for the recovery following the 2008 recession. He oversaw the entire $787 billion stimulus program, speaking with hundreds of mayors nationwide while assessing infrastructure proposals and obsessing over the possibility (or appearance) of corruption. The experience of overseeing a complicated infrastructure spending program previews the work he will have to do as president to coordinate the coronavirus response. In the White House, Obama valued his quality of questioning assumptions and finding “deal space” within complex disagreements.

The themes of competence and moderation were the centerpiece of Biden’s campaign. His campaign strategy was a low risk one: he hoped to win back the white working class of the battleground states Clinton lost in 2016. “Pennsylvania is critical to this election,” he noted straightforwardly in his Nov. 2 Philadelphia stump speech. (Before the election, poll analysts like Nate Silver said Pennsylvania, as the likeliest Electoral College tipping point state, was as important as several other swing states put together.) Biden’s campaign was optimistic, yet realistic, about his paths to victory in the electoral college.

Like during his Senate career, Biden’s policy prescriptions this campaign mostly emphasized moderation. Especially given the uncertainty wrought by the Covid-19 pandemic, his campaign bet that a message of stability would attract moderates while still turning out Democratic partisans. “Do I look like a socialist with a soft spot for rioters?” he said in August. He often reminds voters of his role – or at least, his presence – in the relative calm of the Obama years. “I was with Barack yesterday,” he says occasionally in stump speeches.

Throughout the campaign, he has marketed his competence by releasing a detailed policy agenda regarding Covid-19, healthcare, race, and other issues important to Americans. He spoke knowledgeably about his policy ideas in a refreshingly boring October 16 town hall on ABC News. In a made-for-TV moment, he even stayed after the cameras stopped rolling to keep talking to voters. Despite his stutter and his bumbling reputation, Biden during the town hall adeptly teased out the crux of complex issues and identified trends like the barriers Black Americans face in the accumulation of wealth.

In fact, Biden has a reputation in Washington as being a bit long-winded. James Comey wrote in his memoir that a typical Biden conversation originates in “Direction A” before heading in “Direction Z.” When meeting with him, colleagues leave an extra “Biden hour” in their schedules for talking. When Obama offered Biden a spot as his running mate, he told him “I want your point of view, Joe. I just want it in ten-minute increments, not sixty-minute increments.”

Not only is he prone to meandering, but he has also come to be known for the countless gaffes he has made throughout his career. A few highlights are when he was caught on mic calling the Affordable Care Act a “big fucking deal,” prematurely warned people not to fly during the H1N1 crisis, said the Obama Administration had a 30% chance of getting the Financial Crisis recovery wrong, and called payday lenders “Shylocks” – all during his vice presidency. During this campaign, the most talked-about off-color comment was Biden telling Charlamagne tha God “you ain’t Black” if you support Trump. Biden has a long history of putting his foot in his mouth, and that is unlikely to stop with his election.

Biden’s occasionally cynical, no-bullshit takes may be influenced by the horrific personal tragedies he has experienced. In December of 1972, a month after he was first elected to the Senate and before he was even sworn in, his wife Neilia and baby daughter Naomi died in a car accident. During his first several years in the Senate as a single father he returned home to Delaware via an hour-and-a-half Amtrak every day to see his sons Hunter and Beau. After his first presidential campaign ended in 1987, he suffered a brain aneurysm that left him bed-ridden for three months. After he recovered, he felt he had been given a “second chance in life.” Most recently, his son Beau died of a brain tumor in 2015; the death contributed to Biden’s decision not to run for president in 2016. These tragedies have been a driver of Biden’s career: “I know the pain of burying a son. You’ve got to find purpose when you lose a child,” he said Nov. 2 in Philadelphia.

III. THE CHALLENGES, THE AGENDA

The Biden administration will face challenges on many fronts. The Covid-19 pandemic is worsening again in a “third wave.” The economic recovery, already far from complete, shows signs of stalling. Millions of Americans face issues obtaining affordable healthcare. The left wing of his party is calling on him to pack the Supreme Court to neutralize its newfound 6-3 conservative majority. The killing of George Floyd has crystallized frustrations with decades of police brutality against Black Americans. In short, 2020 has been a disaster so far and Americans will look to Biden to act decisively to make up for the political decadence of the last four years.

Biden is clear that he does not fit the traditional progressive mold: “I beat the socialist,” he said in September. But Covid-19 required the campaign to take on an urgent tone, and in response, Biden has adopted the most progressive political agenda for a Democratic presidential candidate in decades. He was moderate in the primaries, but drifted left in the general, flipping the usual script. Today, Biden supports curbing qualified immunity (but not defunding the police); expanding the welfare state, including doubling Pell grants and investing $100 billion in affordable housing; a public option for healthcare (but not the abolition of private insurance); and entirely carbon-free power by 2035. Biden’s willingness to embrace some central progressive aims made Bernie Sanders’s endorsement of Biden seem easier than his endorsement of Hillary Clinton was in 2016.

More philosophically, Biden faces the challenge of repairing the country after Trumpism. He must restore faith in institutions ranging from the Supreme Court to the Census to the Department of Justice. He will have to restore the friendship of international allies, and frankly, apologize to them. He will need to deal with the epidemic of white nationalist terrorism in this country. The problems of Trumpism do not end with Trump’s political career.

IV. WHAT TO EXPECT WHEN YOU’VE ELECTED

What can you expect now that it looks like Biden has won?

FROM NOW ‘TIL INAUGURATION

First, the Biden campaign will begin the task of fighting chicanery by the Trump administration meant to prevent fair votes from being counted. The Trump misinformation campaign began long before Election Day – the president has misleadingly questioned the validity of mail-in ballots for weeks. On Sunday, Trump campaign senior adviser Jason Miller said on ABC News that the Trump campaign would declare victory based on the votes counted on Election Night even if mail-in ballots had not been counted. That harrowing prophecy came true early Wednesday morning: speaking to supporters in the White House just before 3 a.m., President Trump said, “We were getting ready to win this election – frankly, we did win this election.”

Myriad legal battles are brewing. Courts on Monday narrowly stopped Republicans from throwing out drive-through votes in Texas, and Republicans have sued county officials in Pennsylvania for allowing voters to fix problems with their ballots before Election Day. The Biden-Harris campaign luckily has a massive war chest left over earmarked for these legal battles and has assembled an “army of attorneys” to ensure the election is fairly decided.

When (if?) the result is no longer in question, President-elect Biden will begin immediately to set up his administration. The nominations to Cabinet positions and White House roles like chief of staff which will trickle in until Inauguration Day will reveal how progressive his administration may turn out to be. Starting now, Biden’s every action will try to thread the needle between pleasing progressives and keeping moderates.

Traditionally, presidents-elect set up transition teams after Election Day to begin choosing candidates for federal government positions. Trump picked Chris Christie to lead his transition team – not a good sign right already – and according to Michael Lewis’s The Fifth Risk, ended up shutting the operation down because of how much money he thought it was diverting from his own campaign fund.

Biden will almost certainly follow tradition and use the time between now and Inauguration Day, Wednesday, January 20, 2021, to vet political appointees and set up management structures for the countless endlessly complex agencies within the Federal Government. The Center for Presidential Transition says that transition teams should aim to select key White House personnel and nominees for the top 50 Senate-confirmed positions before Thanksgiving. Pundits say Biden is likely to pick establishment choices for the top roles like secretary of state, which is likely to go to Obama’s national security adviser Susan Rice. However, progressives are candidates for other roles, such as Elizabeth Warren for Treasury secretary. Doug Jones, who lost his Senate race in Alabama last night, is a likely pick for attorney general. Biden promises the “most progressive administration since FDR,” but surely will appease moderates and the Republican-controlled Senate by giving the most important (if not all) roles to safe picks.

If one thing is certain, it’s that disease expert Anthony Fauci will have a job in the Biden Administration: a day after Trump said he would fire Fauci, Biden said he would hire him.

And as Trump begins his lame duck session, the power dynamic between Biden and antagonistic media like Fox News will change. Beginning now, Trump’s foremost cheerleaders will be on their back foot – they are sure to ramp up attacks on Biden for his age, his perceived radicalism, and his stutter. It might remind one of the Obama era where wearing a tan suit or liking Dijon mustard were the biggest scandals of the day. Mainstream news outlets never adapted comfortably to the Trump presidency. (Can you say the word “pussy” on CNN? Can you put “shithole” in a New York Times headline?) Without ever fully resolving questions like those, journalism will return to its comfort zone during the Biden administration. The press will be free from Trump’s repeated attacks on its credibility and will no longer have to grapple with how to cover the norm-breaking Trump administration.

THE FIRST HUNDRED DAYS

Every presidential administration since FDR has been expected to use its first hundred days to rack up accomplishments and embark on an ambitious legislative agenda. Biden’s first hundred are likely to be largely absorbed by his Covid-19 response. But Obama, too, was dealt a bad hand – two wars and a financial crisis – and still dabbled in trying to close Guantanamo Bay and preserve climate change treaties, among other things, within his first hundred days. Obama, however, had majorities at the outset in both chambers of Congress. Democrats’ disappointing failure to take control of the Senate rules out progressive objectives like D.C./P.R. statehood or Supreme Court packing; President Biden will be confined largely to the realm of executive orders for his first two years (if not more).

Nonetheless, as best he can, Biden will immediately begin implementing his comprehensive Covid-19 plan, which includes huge investments in testing (including at-home testing) and PPE distribution as well as a national mask mandate. Another top priority will be the economy more directly. He plans to extend aid to state and local governments and broaden unemployment insurance, among other measures. Other issues which were major campaign questions, like Supreme Court packing, will be conspicuously absent from his first hundred days. He reveres institutional tradition, and given Republican control of the Senate he is unlikely to try to pack the Supreme Court or make major changes like term limits. His “commission to study reforms,” if it materializes, is unlikely to result in any.

Another thorny question Biden will hope to avoid is what to do about Donald Trump. Progressives will want to investigate the Trump administration and pursue Trump himself for prosecution. Biden, who was in his first term in the Senate when Gerald Ford infamously pardoned Richard Nixon after Watergate, has promised not to pardon Donald Trump as president. Publicly, he will leave the question of whether to prosecute Trump to his Attorney General, but as a skilled political salesman, he will do everything he can not to let lingering questions about Donald Trump distract from his own presidency.

THE NEXT FOUR YEARS

Biden’s goal over the next four years will be to set up the Democratic party for the future. He will need to walk a fine line to please both the increasingly vocal left wing of the party and the moderates who will remember his 2019 promise that “nothing would fundamentally change” if he were elected. His policies will likely disappoint the left but achieve and build upon some unrealized goals of the Obama administration.

Foremost of these, and one of the most important issues to voters, is healthcare. Biden has promised to build on the successes of the Affordable Care Act to introduce “Bidencare,” a public health insurance option like Medicare, while increasing health insurance tax credits and attempting to protect preexisting conditions. Apart from that, hopes to increase the federal minimum wage to $15/hour, eliminate tuition at public colleges for students from households earning less than $125,000, and triple the money the federal government sends to low-income schools.

These would be meaningful, if incremental, changes, which could allow the Biden administration to preserve a fragile electoral coalition and lead the party toward success in 2022, 2024, and beyond. In May he began referring to himself as a “transition candidate,” and the choice of Kamala Harris as his running mate was an olive branch to the next generation of the Democratic party. But as his polling looked favorable in recent months, his tune shifted: he said in August that he would “absolutely” be open to running for another term. (In 2024, he’ll be 82.)

V. EPILOGUE

Election morning, Biden visited Beau’s grave in Wilmington as well as his childhood home. On the wall of the house he grew up in – before his four-decade Senate career, before his two terms as vice president, before three presidential runs (one successful), before the tragic deaths of a wife and two children, he wrote the following:

“From this house to the White House with the grace of God.

Joe Biden 11-3-2020“